This is not a device. It's an invitation to explore the frontier.

Recently, the Rabbit r1 launched. It's a new handheld device that promises a new primary interaction model with compute: by talking to them in the context of the real world. In turn, they would help us perform actions to help us with unstructured, but menial tasks throughout our day.

The reaction was visceral. As evidenced by the entire thread of replies, otherwise reasonable people were overcome by unreasonable emotion against someone building something categorically new.

Hot take: NO ONE actually wants AI to:

— Matt Van Swol (@matt_vanswol) January 10, 2024

1) Book their vacations

2) Order a random pizza

3) Have access to their bank account

Why are we creating tech no one wants? pic.twitter.com/nvwlBxv1HN

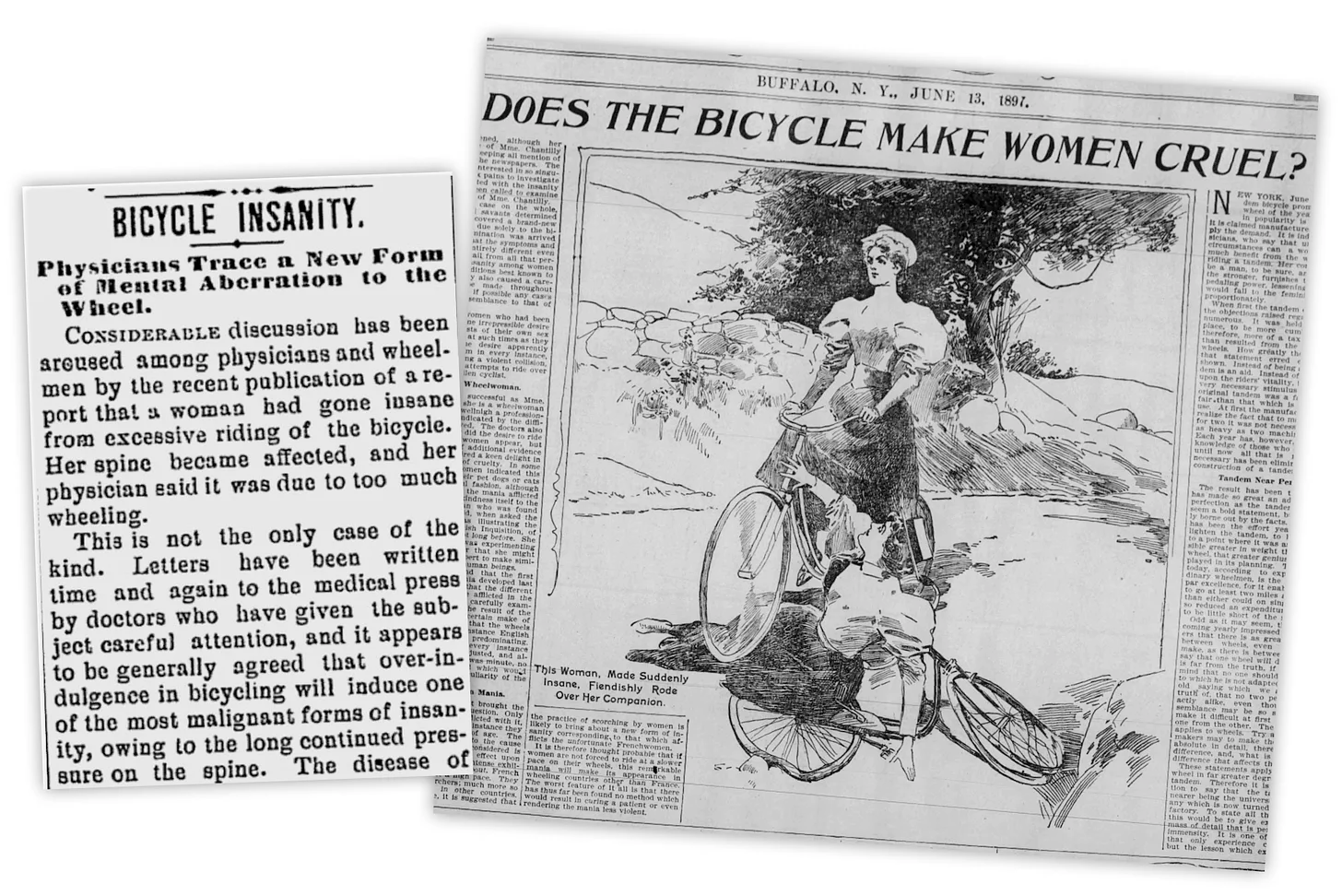

Of course, hot takes for internet points is nothing new, and it has no cost to take up a dissenting view. But there's this insidious underlying pessimism whenever we introduce something categorically new: why are we making tech where I can't see the need?

I had originally set out to write about the pessimistic reaction to the Rabbit r1 (having no affiliation with the company), but this expanded to an expression of my broader view: that technological optimism is required for seeing into the future for the health of both the individual and society.

Surprisingly, I find this cynical perspective common even among tech workers, the people supposedly building the future.[^0] Our collective memories are so short that we can't remember how obviously useful technology started as toys with non-obvious utility. As if the technologies one uses today weren't once radical heresies that transformed into an ambient miracle we take for granted. And as a technology optimist, I find it incredibly shortsighted to dismiss anything outright.

Here's where one might object: it's selective bias if we only look backward! Of course, that will make it seem all heretical new inventions will become commonplace. What about all the different technological innovations that failed?

I'm not suggesting that every new thing that comes on the market has an inevitable climb to being indispensable and commonplace. But I am saying for categorically new technology, we can't tell just by thinking about it.

For sustaining technologies that have an existing market of jobs-to-be-done, we can accurately tell whether we can make use of a new technology or not. When a new smartphone comes on the market today, it does mostly the same job that I've used other smartphones for before. Take pictures, chat with friends, navigate the world, check email, troll on social media, or hail a ride. I can accurately predict whether I'd find any of these useful because it's easier to imagine something I'm already doing, but better.

But for potentially disruptive and categorically new technology that addresses completely new and underserved markets, it's very hard to see or predict where the utility will be. By definition, technology that caters to new and underserved markets addresses our changing habits, boosts our capabilities, or expands our possibilities–something different from what we do now. Unless you happen to be smack middle of the underserved niche, it won't be obvious how a categorically new technology is useful. It takes work to move yourself into the niche to see a new technology's potential.

When the iPhone first came out, the biggest objection was its lack of a physical keyboard. But with additional predictive technology, a device with no keyboard was usable without fanfare. Initial objections loom so large in the pessimist's mind that they can't get beyond it to ask more forward-looking questions–to move themselves into the niche of a categorically new product. Doing so is to explore, to say to oneself, "What if this did work? Then what?"

An explorer would notice that a multitouch interface expands the set of mobile applications beyond email. Then the forward-looking question was, "What mobile applications does this enable?" An explorer would see the smartphone made computing intensely personal for the first time by being always on you in your pocket. Then the forward-looking question was, "How does this affect how people view each other or themselves?" It may not be clear what the answers are, but at least you're starting to ask targeted questions about the future. Because, unlike technology in existing markets, it's hard for us to imagine something we've never done before.

Hence, this is my own hot take: The Rabbit r1 isn't a device. It's an invitation to explore a new frontier.

All is not lost

Well, not everyone is pessimistic. Rabbit sold 10k devices invitations to explore on the first day, and sold out of 5 batches.

What I'm excited about the Rabbit r1 is that it brings real-world context into an LLM. My own experiences with LLMs conclude context is very important for LLMs to be useful. To that end, we currently pair a search over a database (Retrieval Augmented Generation, RAG) with an LLM. But we can pair it with more than just a database. Rabbit provides a multimodal context of the real world. It makes the real world a "database" that an LLM can query, and that opens up many categorically different use cases than we've had in the past year using LLMs in a chatroom context.

And lots of people on this thread have positive outlooks about its prospects too.

lots of folks coming down hard on rabbit.

— Aaron Ng (@localghost) January 10, 2024

i'd rather live in a world with more stuff like this being made, wouldn't you? https://t.co/pWMoMuVcGe

People are so used to a mature market where they get a handful of iterative/boring devices a year

— Ben South (@bnj) January 10, 2024

News flash: we’re in the midst of a paradigm shift and we get to have fun again

Great point! We all want innovation and competitors, and even if big companies can do it better, I’ll support the small companies on principle and knowing there’s always gems 💎 to be found.

— AlphaRomeoSierra (@ARomeoSierra) January 11, 2024

Great to see folks trying things and opening our eyes to possibilities. Not all will be here long term but they do provide something to build on and perhaps help us rethink how we get through our day.

— Gary Greco (@garyzface) January 10, 2024

There are still explorers of frontiers out there, looking towards the future. I think it's important that we keep that sense of excitement for the future alive. Technology doesn't progress all on its own. It only happens when people who see a problem are motivated to find a solution, either by using one or by creating one.

Why is seeing the future important? How do you set yourself up to have the greatest chance of seeing the future?

If you want to hear more on this line of thought about optimism and seeing the future, subscribe or follow me on Twitter.

Thanks to Eric Dementhon for reading the drafts.

[^0] For non-tech workers, I find disruptive innovative tech doesn't even register in their heads. They don't even know what they're looking at when you show it to them.